Art Detective: Cleobis and Biton

- Alexandra Smith

- 14 minutes ago

- 5 min read

By Alexandra Smith

"Cleobis and Biton" is an intensely dramatic artwork painted in 1884 by Carl Ernst von Stetten (1857-1942). I’ve been thinking about it for months, ever since it stole the show in 'Renaissance, Romanticism, and Rebellion' at the Mint Museum Uptown location.

The scene is set at a Greek temple, stone columns rising in the background. Two young men lie together, seemingly unconscious, on top of a red blanket. They are each wearing a crown of laurels and a loincloth-type garment. A statue towers above their heads, and the altar, dressed with flowers, stands at their feet. A group of women clad in white robes is entering through a doorway, and the one in front looks both shocked and dismayed.

The title of the piece points directly to a short story inside Herodotus' Histories, involving two young brothers who were bestowed the "blessing" of death by the goddess Hera as a reward for carting their priestess mother five miles to the temple for a festival. In the tale, the brothers are referred to as two of the three happiest men in the world, dying peacefully before knowing anything of life’s hardships.

Carl Ernst von Stetten was a German painter who spent most of his career in France, which spanned from the 1880s to the 1910s. I believe fewer than 30 of his pieces are known to survive today.

"Cleobis and Biton" is one of his largest works, clocking at over five feet tall and seven feet long. With this piece, he won his first medal, much to the chagrin of the savage writers at French newspaper Le Petit Parisien. I found a clipping that states:

"Mr. Carl von Stetten's painting is, in fact, utterly mediocre. It doesn't even deserve a look."

Well, excuse me. Talk about drama! Now I'll admit that when I first saw this piece, I made up an entirely different story. I saw two lovers asleep after a secret tryst in the temple, only to be discovered in the morning. Why? I didn't find a compelling reason to interpret the bodies as corpses. And I don't know of any brothers that fall asleep together, let alone cuddling. It came across as a different kind of love and intimacy.

I found myself wanting to know more. Through my research, I discovered that other artists have also depicted this story. The earliest known example appears as a pair of marble statues dedicated at Delphi by the people of Argos around 610 BCE (approximately 185 years before Herodotus wrote his Histories).

This tells us that almost two centuries of oral and written tradition had to be passed down for Herodotus to hear the story and include a version of it in his tales. And now, over 2,000 years later, we remember. Art is the reason.

A closer look at these stone brothers may inform the way von Stetten painted the scene. The statues are an example of "heroic nudity," a Classical concept in which heroes, warriors, gods, and nobles are depicted with an idealized version of their nude bodies. See Michelangelo's "David" and Rodin's "The Thinker" for additional representations.

While he was trained in academic historicism, von Stetten approached classical subjects through a lens shaped by the Neoclassical revival movement sweeping through France. The partially clothed bodies in "Cleobis and Biton" reflect this influence, balancing idealized form and moral symbolism.

Could there be other explanations? I learned that von Stetten had a “close relationship” with two artists: Gustave Courtois and Pascale Adolphe Jean Dagnan-Bouveret. They all met when they each came to study at the École des Beaux-Arts. Over the years, they shared studios and living space, and often posed for each other’s pieces.

There's a drawing entitled "Laundress (La Blanchisseuse)" by Dagnan-Bouveret that shows our painter walking together with Courtois, arms interlocked. Analyses over the years have said the scene shows a weary working-class woman judged by two high-class men for being poor, and possibly a prostitute. One takes the other’s arm to “lead him away.”

A painting of this study was presented in the 2025 Chicago exhibition, 'The First Homosexuals: The Birth of a New Identity, 1869-1939.' Backed by research from art historian André Dombrowski, the curators assert that this is the first known depiction of a modern gay male couple in European art.

Learning this makes me wonder if the drawing was a small act of rebellion. Perhaps the artist is saying, “I look down on you for living an unfulfilled life. I am the richest man here.” Perhaps the painting holds up a mirror to two groups of people, each oppressed by larger society. Or maybe it’s just a commentary on the judgment that accompanies poverty. I have no real answers. Seen in this context, von Stetten’s painting may have provided a place in which male intimacy could be explored within more "acceptable" historical and classical frameworks.

We don’t even know for sure that any of these men were gay. In the end, it doesn’t matter. We do know that each of them had a special talent for depicting the male body with profound beauty and tenderness. And that these classical ideals were actively constructed in the studio through the bodies artists chose to study and depict.

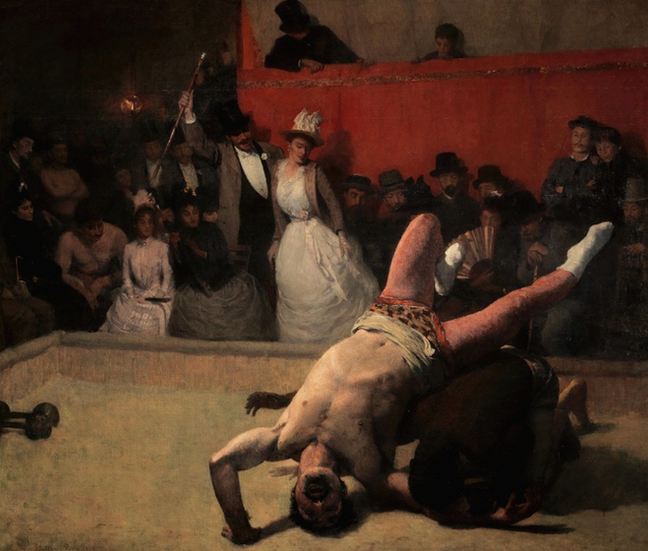

When they were not posing for one another, von Stetten and his circle often turned to professional strongmen like Maurice Deriaz, a Swiss wrestler who once defeated forty-four opponents in a single tournament. I don’t think it’s any coincidence that the sport of Greco-Roman wrestling surged in step with the Neoclassicism movement. So back to our dear boys Cleobis and Biton. Is the painting based on real brothers? Or an old Greek legend? Was von Stetten unable to express his ideas freely, using his artwork as a code? Did his chosen models ooze sensuality despite the prescribed scene? Or did he layer his own memory into the painting?

I'm also tempted to wonder whether von Stetten briefly entertained a darker thought: that it might be better to be dead than deny who you truly are. Better to die young before having to pretend you're not different.

All of this inner dialogue makes me think of living authors who, after having the intense symbology of their work analyzed in English class, come out and say something to the effect of, “I just like the color blue.”

And so here we are at the end, with more questions than answers. We’ve travelled from Charlotte to Ancient Greece to 1880s Paris. Through this artistic wormhole, we’ve discovered three artists and seen dozens of their works. We’ve touched on subjects including sacrifice, goddesses and temples, heroic nudity, poverty, wrestling, death, and more. And we’ve interrogated our own assumptions surrounding masculinity, queerness, nudity, and intimacy.

Art serves as a portal to places we can’t imagine until we get there.

----------------------

Sources:

Herodontus' Histories, Book 1, Chapter 31

Newspaper clipping

Brother statues

Laundress drawing

Weisberg, G. P., Dagnan-Bouveret, P. (2002). Against the Modern: Dagnan-Bouveret and the Transformation of the Academic Tradition. United States: Dahesh Museum of Art.

Lubow, Arthur. “How ‘Gay’ Became an Identity in Art.” The New York Times, 12 July 2025, Arts section.

Harrity, Christopher. “A Portrait of Intimacy.” Advocate, 12 July 2014